Spreading the Allure of Glass Art from Toyama, a City of Glass Art

Interview with an expert

We asked Ms. Ruriko Tsuchida, Director of the Toyama Glass Art Museum, about the lesser-known historical background of glass, the relationship between glass and people, and its cultural value. She also talked about the allure and depth of glass art and her vision and belief as a curator of outreach and engagement.

Ms. Ruriko Tsuchida, Director of the Toyama Glass Art Museum

She has planned many glass-related exhibitions, including ones featuring Émile Gallé and Satsuma Kiriko (cut glass). In 2009, she won the Academic Prize of the Western Art Foundation Prize and the 30th Japonism Society Award for her distinguished service in organizing the Gallé and Japonism exhibition (organized in 2008). Her books include Kiriko KIRIKO Japanology Collection published by Kadokawa Corporation; The Concise History of World Glass, supervised by Kimio Nakayama and published by Bijutsu Shuppan-sha Co., Ltd. (co-authored); and KAWADE Mook: Definitive Edition Emile Gallé’s Glass, edited by Ikunobu Yamane and published by Kawade Shobo Shinsha (co-authored).

She serves as the chair of ICOM Glass and a board member of the Association for Glass Art Studies, Japan.

1967 Born in Tokyo1992 Completed a master’s degree in aesthetics and art history, philosophy major, Graduate School of Letters, Keio University

1992 Started to work for Suntory Museum of Art

2010 Curator in Chief for Suntory Museum of Art

2020 Deputy Director, Toyama Glass Art Museum

2022 Director, Toyotama Glass Art Museum (current position)

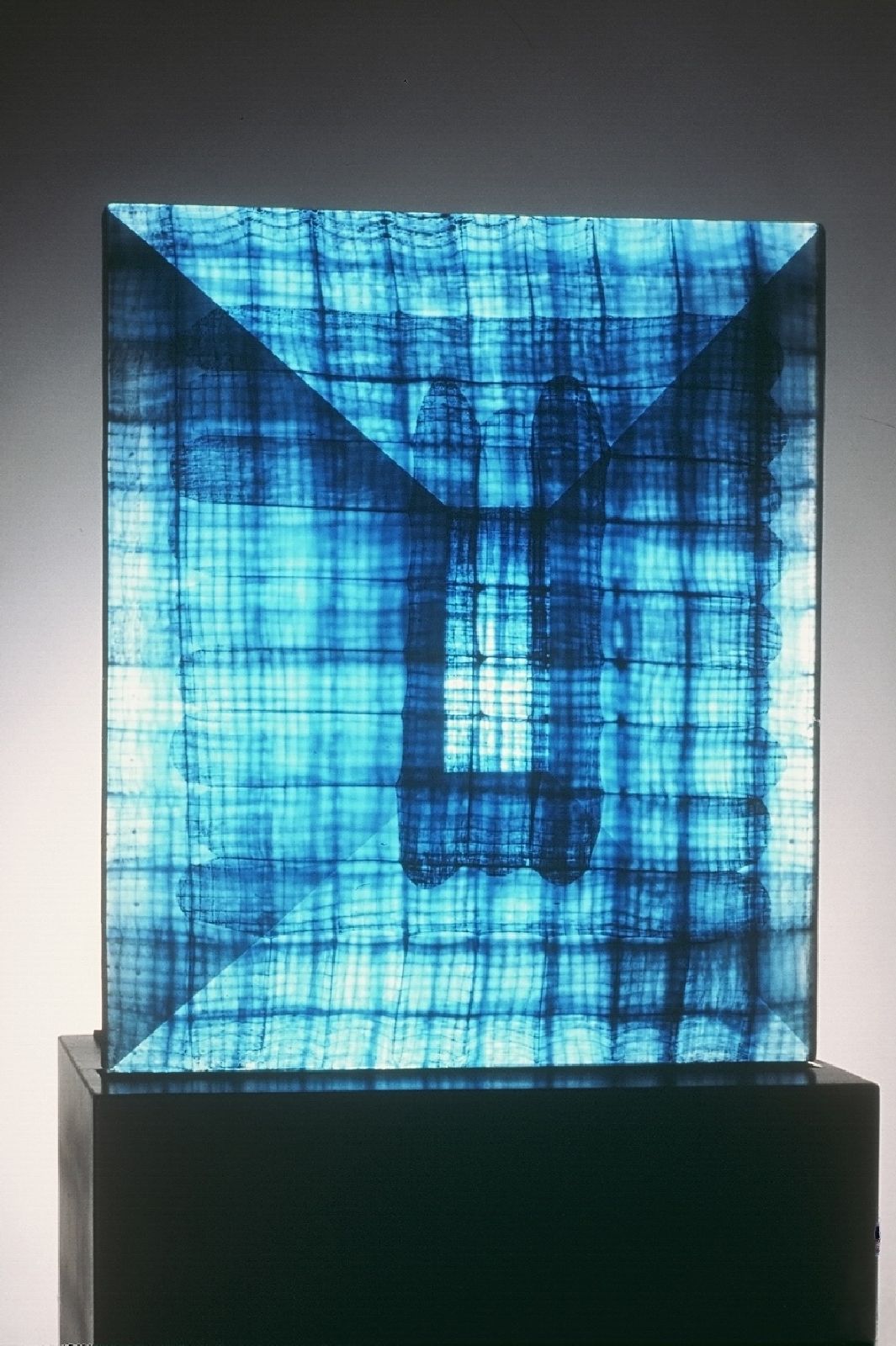

1993–1995, photo: Taku Saiki, in the collection of the Toyama Glass Art Museum

Discovering the allure of glass art at the Suntory Museum of Art

—How did you discover the allure of glass art?

I was named Ruriko because my maternal grandmother considered it phonetically pleasing. Ruri in Japanese refers to lapis lazuli, a beautiful blue rock, glass of the same color, and the color of deep blue. My parents also liked the name because it is derived from glass, which shines when polished. Because I was told how I was named, I found glass somewhat intriguing in my childhood. I felt close to things related to glass, such as marbles, ohajiki (small coin-shaped pieces), and the color blue.

I developed an interest in art after I entered college. I specialized in art nouveau for two years at graduate school. It was extremely difficult to find a job at a museum. Notably, the world of art was dominated by men at the time. There were few female curators. I secured a job at the Suntory Museum of Art as a female staff member, not as a curator. I assisted male curators serving as a receptionist, gallery attendant, and accounting clerk.

Among art museums featuring antiques, the Suntory Museum of Art had a large collection of glass art in particular. Glass works accounted for about one third of the 3,000 items in the collection. A few years after I joined the company, the museum acquired glass works mainly of Émile Gallé, which were collected by Yasunari Kikuchi who was a private medical practitioner in Hokkaido. With the significant expansion of the glass art collection, it was decided to hold a Gallé exhibition. At the time, there was little literature on glass works available in Japanese. I was assigned the task of conducting preliminary research for the exhibition because I had studied French as a second foreign language. As I learned more about glass art, I was drawn into its profound, beautiful world.

The development of glass art through interactions between different cultures over 5,000 years

—What is the influence and significance of the history of glass art for people's lives and cultures?

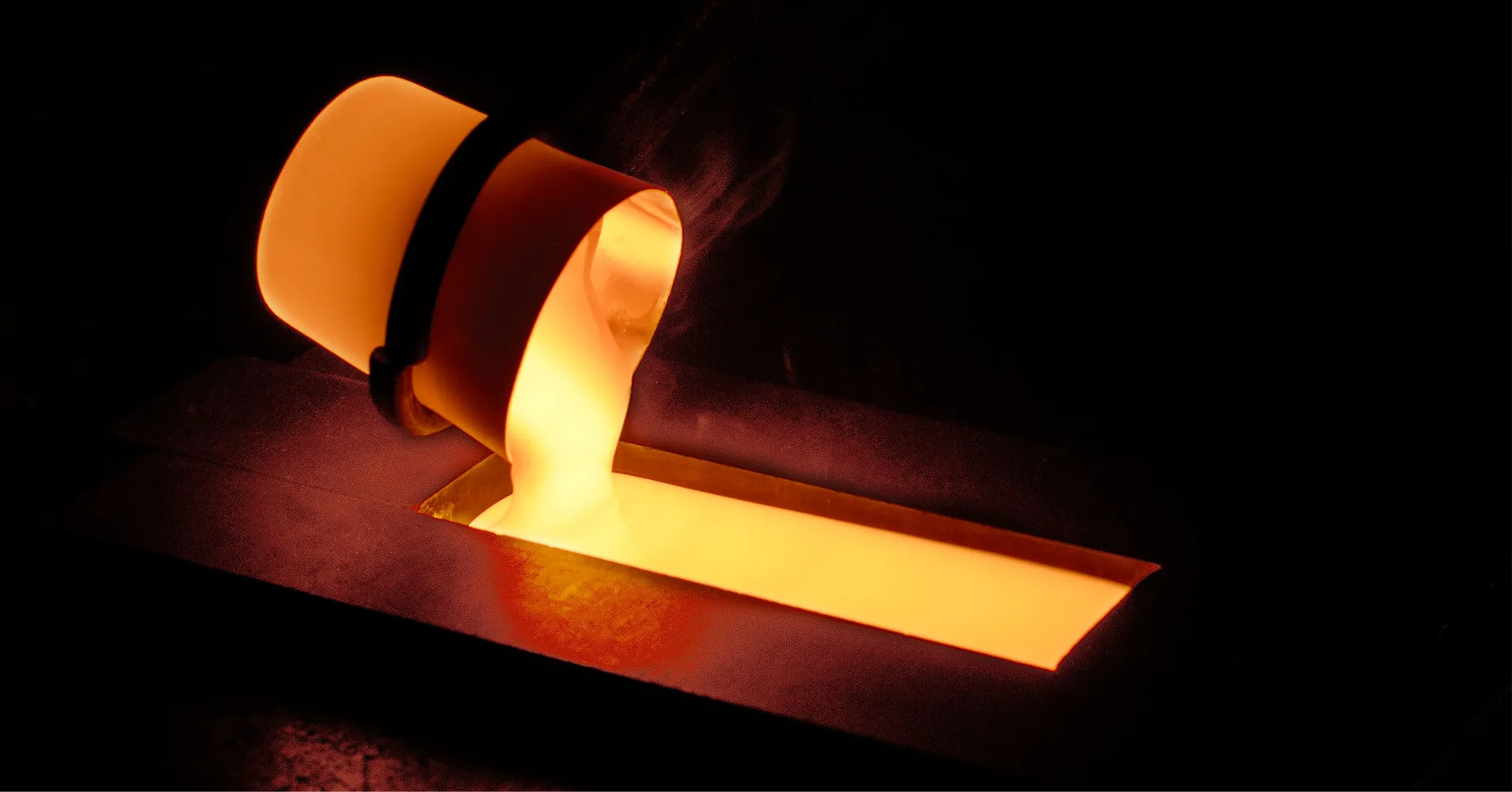

The history of glass dates back about 5,000 years. Glass products were already produced in ancient Rome. They spread rapidly due mainly to the invention of the glassblowing technique around 1 BC.

Obsidian, a natural glass, is a type of volcanic rock formed when magma cools rapidly. It is generally black in color because it contains various mineral components. Highly transparent glass, which is widely used today, is made mainly from silica sand, a main component of the Earth’s crust. It requires extensive chemical knowledge and processes specific to glass, such as the addition of fluxes for refining raw materials and lowering the melting temperature, and stabilizers for increasing durability. This is probably one of the factors that prevented the spread of glass art compared to pottery.

Generally, art flourishes with the financial power of patron rulers and social stability. Glass art is no exception. The opaque core glass technique was developed during the 18th Dynasty of Ancient Egypt. In the 15th century, Venice prospered through transit trade. Artisans who fled from the Middle East, including Damascus, brought advanced techniques to Venice. Venetian glass is characterized by cristallo, a material that was almost colorless at the time. Due to its high transparency, it was acclaimed as being like crystal and became extremely popular as ornaments for the nobility. A milky white glass called “Lattimo” was also developed, and its combination with clear glass led to the development of glass products with delicate lace patterns. Such luxurious cups and ornaments were treasured by the nobility as symbols of their wealth and power.

In the 17th century, a new glass material containing potassium was developed in Bohemia, giving rise to a new style that marked a departure from Venice. The nobility had their portraits or hunting scenes painted on glass to satisfy their desire to seek attention and demonstrate their social status.

In this way, the development of glass art reflects the historical background and human desire. I find it intellectually stimulating. The Suntory Museum of Art, which has a great collection, guided me from the ground up, but I did not specialize in outreach and engagement regarding glass art. I was born and raised in Tokyo, but why did the Toyama Glass Art Museum need me? I consider it my responsibility to contribute to the mission of the museum, namely, to publicize the allure of glass art from a professional viewpoint.

Mission of the art museum: to immerse visitors in stories

—What are challenges of glass art compared to other art forms, such as painting and pottery?

In Europe and the U.S., glass art is more recognized than in Japan, but it is still in a relatively minor position compared to other art forms. I serve as the chair of the International Committee for Museums and Collections of Glass as a member of the International Council of Museums (ICOM), which is based in Paris. The committee is the smallest within the ICOM. For many people, painting is a familiar art form in their daily lives. Even children enjoy painting. Pottery has become relatively popular across Japan. However, there are few opportunities for glassmaking because special equipment is required to melt glass. This is one of major challenges.

—How do you recognize the beauty and allure of glass art in your daily work?

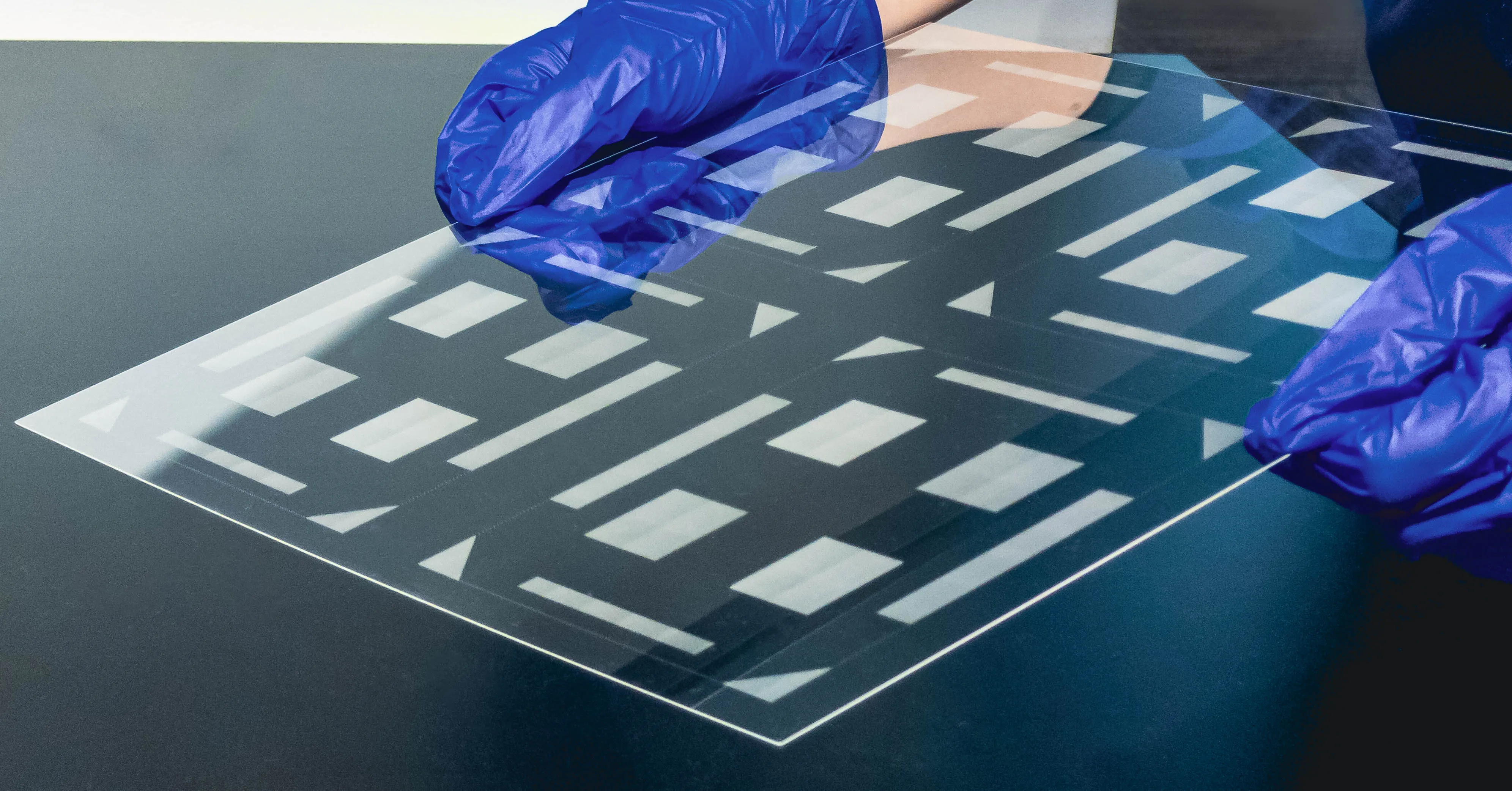

Since I started to work with glass art at the glass art museum, I have come across an increasing number of works that go beyond my conventional concept of glass. Those glass artworks that I previously saw were mostly shaped as containers. Contemporary works vary in shape and color with different textures, including glossy and rough textures. Although the materials are limited, the expressions of glass vary depending on the technique. An increasing number of artists combine glass with other materials. In recent years, we have observed unique attempts to reuse the glass of cathode-ray tubes and building materials, including heat reflective glass panes and solar panels, as well as the knitting of glass fibers by knitting artists. I am often amazed to find some works that I didn’t expect to be made from glass, and discover different characteristics of glass. Diversity represents the most attractive feature and potential of glass art.

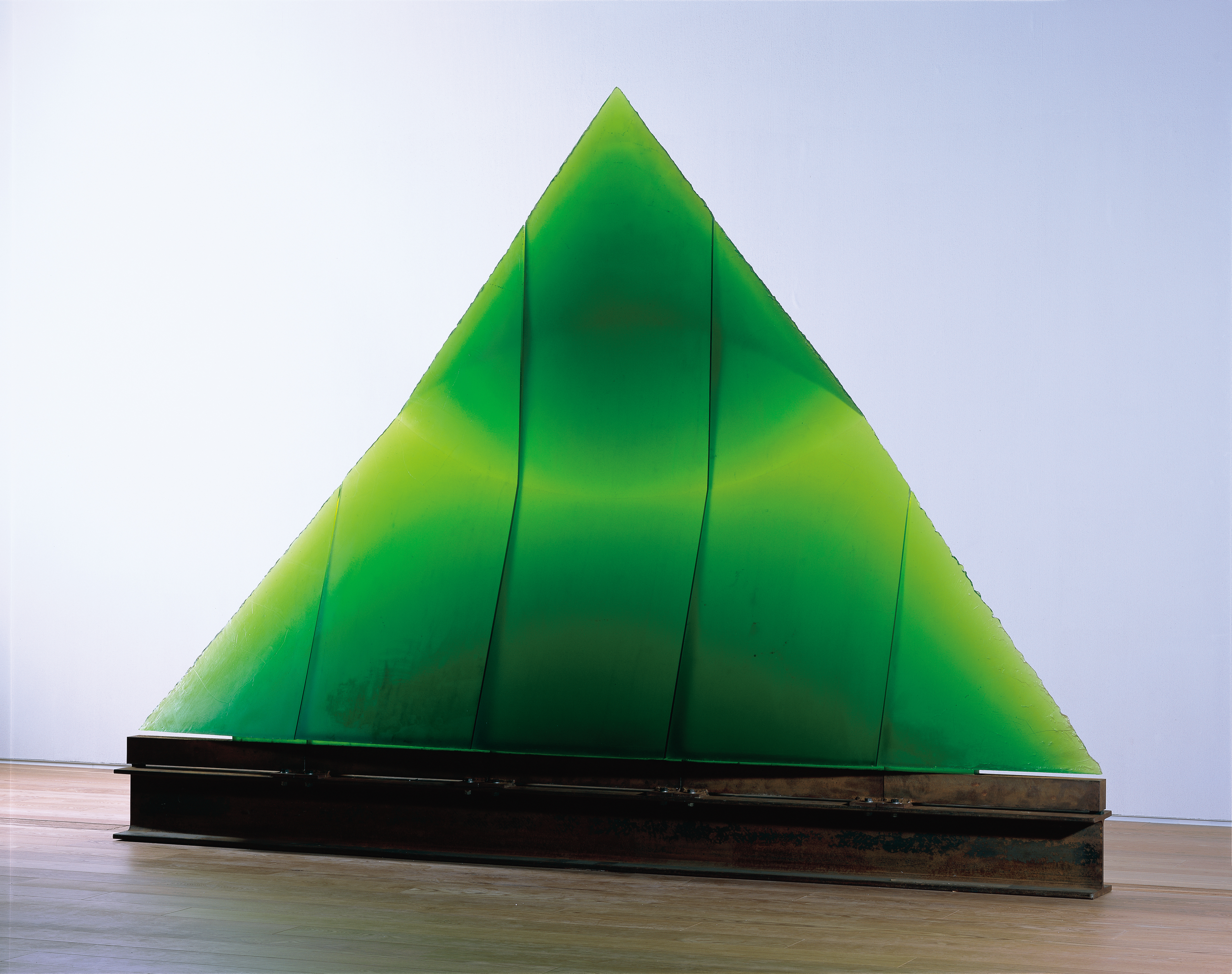

Glass art has a vantage point in the art world in terms of the high degree of freedom without factions or schools, and the absence of rules in terms of technique or expression. Before the 20th century, there was a pronounced tendency to be constrained by national structures. In the 21st century, the sense of belonging of artists has weakened, and personal concepts that transcend national boundaries have come to be strongly reflected in their works. The museum hosts the triennial Toyama International Glass Exhibition. In 2021, during the COVID-19 pandemic, there were works expressing invisible fears. This reminded us that people living in the same era can empathize and communicate across national borders.

—What is your belief in publicizing the allure of glass art?

In contemporary works, priority is placed on originality, concept, and consistency of expression. We want to recognize such works and introduce them to visitors. I expect visitors to the art museum to freely appreciate and interact with each work, allow their minds to resonate with the artist’s vision, and let the work evoke a mindscape.

A curator serves as a mediator who creates stories through the composition of an exhibition and provides a new perspective to visitors. You cannot communicate what you do not understand yourself, so I tell curators to fully understand the works before formulating plans. I also advise them to arrange easy-to-understand works at the entrance and organize works in chapters so that visitors can readily connect with stories.

The role of the art museum is to showcase the beauty of the respective works using the exhibition space as a medium and immerse visitors in stories. Visitors may feel that they get the point in the final chapter of an exhibition. Even if they do not, we are glad as long as they are impressed by one or two works.

Toyama, City of Glass Art, with as many as three glass art facilities

—What are some of your future initiatives? What is your vision and commitment toward the development of glass art?

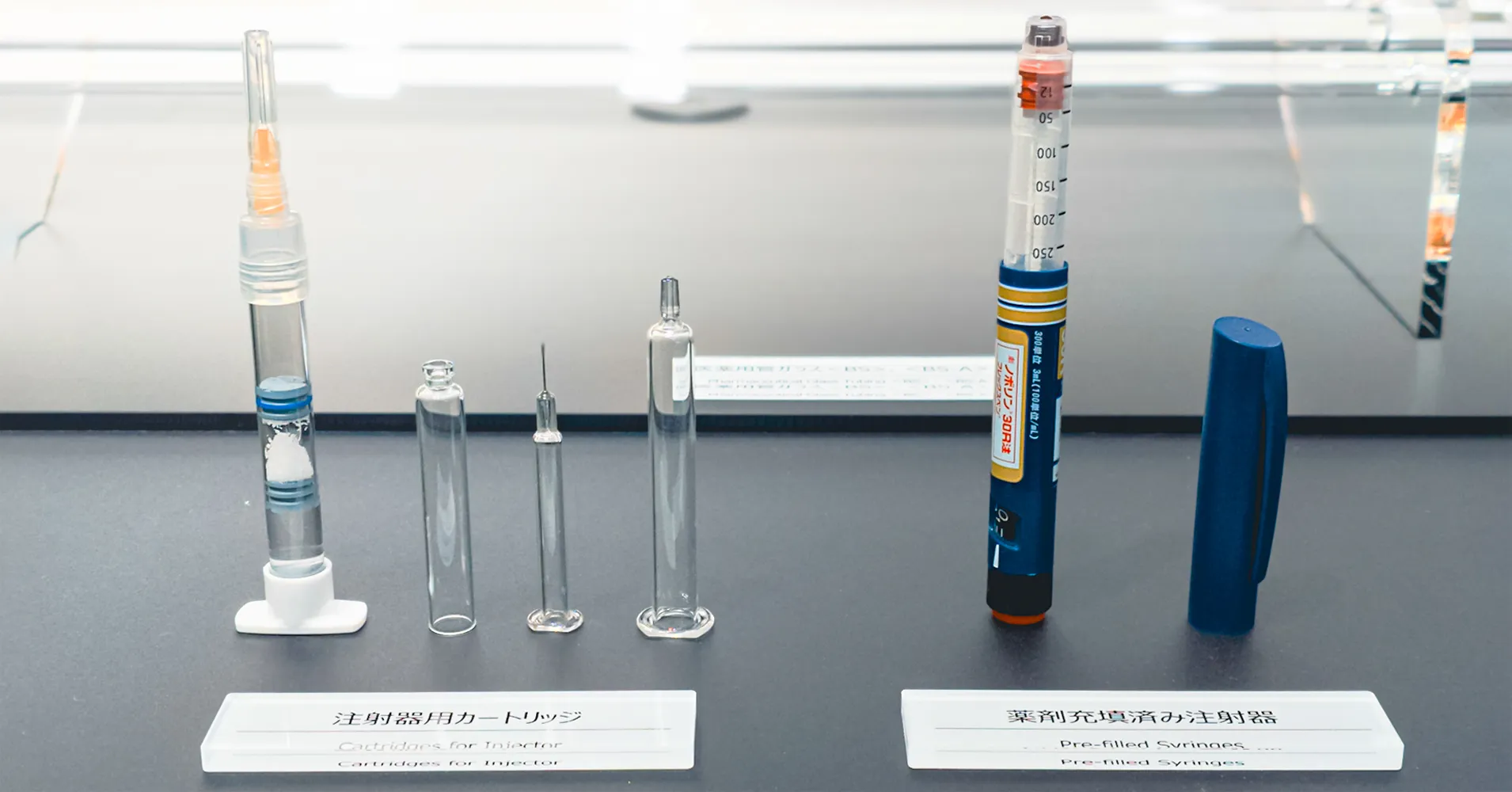

Toyama City is home to three glass-related facilities. Toyama Institute of Glass Art was established in 1991 to nurture glass artists. Toyama Glass Studio was opened in 1994. The Toyama Glass Art Museum was opened in 2015. Few cities in the world have a glass-related institute, studio, and art museum. Being a rare city with these facilities, the City of Toyama brands itself as a city of glass art.

The Toyama Glass Art Museum partnered with the Corning Museum of Glass in New York State. In foreign countries, Toyama is known as Japan’s hub for the dissemination of glass art. However, in Japan, Toyama is not widely recognized as a city of glass art. While these three facilities are well-established, it is necessary to share the city’s vision and strengthen partnerships, and thereby enhance Toyama’s brand image as a city of glass art. Consultations have been held to strengthen partnerships.

While glass artists are engaged in international interactions to some extent, global networks of curators and researchers remain weak. There are interactive opportunities for people engaged in glass art worldwide, but only a small number of Japanese people participate. While the language barrier is a major issue, curators also lack motivation.

For the development of Japan’s glass art, stakeholders should actively participate in the international arena. I am also involved in the development of a global network through the activities of ICOM, and I recognize the benefits. To enrich the exhibitions of the art museum, it is essential to borrow works from overseas collections, but few owners are willing to lend precious works to people they have never met. Face-to-face relationships are the key to facilitating this work. The Toyama Glass Art Museum encourages international interaction by allocating a budget for curators to study abroad. I remain committed to raising the profile of Toyama as a city of glass art and promoting wider international recognition of glass art.

Toyama Glass Art Museum

The glass art museum, which symbolizes “Toyama, City of Glass Art,” is located in the Toyama Kirari complex designed by world-renowned architect Kengo Kuma. It features permanent and special exhibitions of contemporary glass artworks both in and outside Japan, including installation art by Dale Chihuly, a master of contemporary glass art.

Website: Toyama Glass Art Museum