The “Magic Glass” in Your Palm — The Secret of Ultra-thin Glass for Smartphones

By: Takuta Murakami

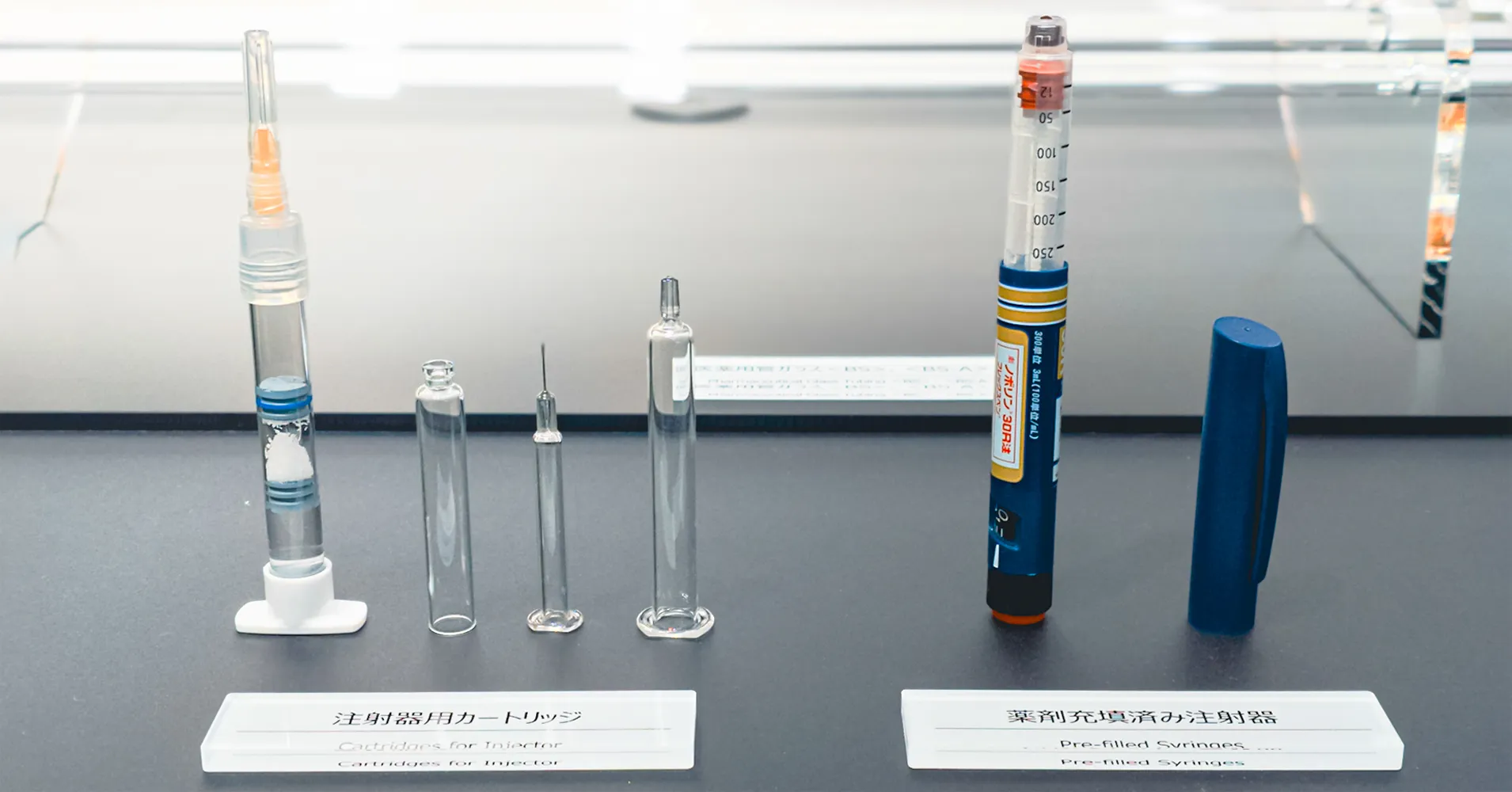

The pharmaceutical container market is currently undergoing a major transformation. While vials and ampoules still dominate the market size, demand for pre-filled syringes and syringe cartridges is rapidly increasing worldwide, driven by efforts to improve efficiency and safety in healthcare settings.

Accelerating this trend is the rapidly growing GLP-1* drug market. The market is expanding at an annual rate of approximately 33%, driving a surge in demand for syringe cartridges that can be directly fitted with the drugs. Adoption is expected to spread not only in Europe and the US but also in emerging markets like China and India, fueling demand for pharmaceutical containers.

At its core is borosilicate glass, known as a material suitable for pharmaceutical containers. It exhibits low reactivity with drugs, excellent heat resistance and chemical resistance, and has become the standard material from a quality assurance perspective.

Behind the everyday products we use without a second thought lies the wisdom of those who developed extraordinary technologies and the dedication of those who support their production. Let’s take a moment to appreciate the display glass of smartphones—devices we can no longer live without even for a day.

The Unbreakable “Magic Glass”

When we think of “the most familiar glass today,” it’s likely the display glass on our smartphones. We look at it and touch it all day long.

Have you ever broken the display glass on your latest smartphone? Of course, glass can still break, but have you noticed that it happens far less often than before? More people are likely to have experienced dropping their phones and thinking, “Wow, it didn’t break!”

Sure, maybe you were just lucky. But in truth, thanks to technological advancements, smartphone display glass has become remarkably resistant to breaking—almost like magic.

You might even think, “Come to think of it, I used to see more people using phones with cracked screens, but not so much anymore.” The cover glass on the latest foldable smartphones is just 0.05 mm thick—or even thinner. Yet, it’s strong enough to withstand drops without breaking easily.

A smartphone’s LCD display typically consists of two substrate glass layers and one cover glass. The substrate glass surface must be extremely smooth to support the display circuitry, while the cover glass assembled on top of it must be highly durable. OLED displays, on the other hand, use one cover glass and zero to two substrate glass layers.

This ultra-thin glass for smartphones is produced using highly advanced technology. Its strength and thinness continue to evolve rapidly. Only a handful of companies worldwide can manufacture this special glass: Corning (USA), SCHOTT (Germany), AGC (Japan), and Nippon Electric Glass (NEG). NEG holds about 20% of the global market share for display glass, competing with AGC for second place behind industry leader Corning.

While Japan may have fallen behind China, Taiwan, and South Korea in the production of smartphones and computers, many of the components that make up these devices are still made in Japan. Ceramic capacitors (Murata Manufacturing), sensors (Sony’s CMOS sensors, TDK, Seiko Epson’s accelerometers, gyroscopes, and geomagnetic sensors), wireless communication modules (Murata, Kyocera), and display glass are just a few examples. Japan has focused on producing “high-precision, hard-to-replicate components,” a strategy that could be considered a national policy.

NEG’s ultra-thin glass for chemical strengthening, Dinorex UTG®, is one such uniquely Japanese product that is in demand worldwide.

Glass Technology and the Techniques of its Production

So, what exactly is glass? And how is ultra-thin glass for smartphones made?

Generally, glass is thought to be made primarily of silicon dioxide (SiO₂), but more precisely, it is an amorphous substance—lacking a crystalline structure and possessing a disordered, liquid-like structure despite being solid.

Ultra-thin glass for chemical strengthening like Dinorex UTG® is made by blending SiO₂ with soda ash (Na₂CO₃), limestone (CaCO₃), boron oxide (B₂O₃), alumina (Al₂O₃), and trace amounts of other components to enhance properties like impact resistance. These are melted and mixed in a furnace at around 1,500°C.

For diseases where effective drugs have been limited until now, pharmaceuticals with superior efficacy to conventional treatments have been developed, raising expectations for these medicines higher than ever before. Examples of drugs developed in recent years are shown below.

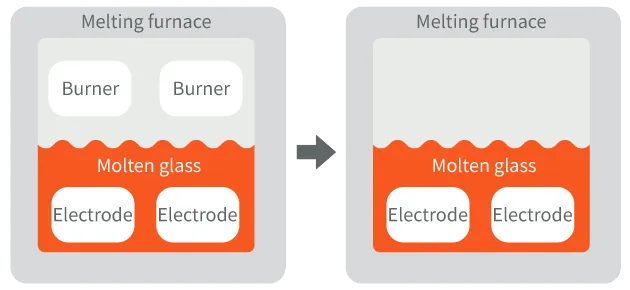

The furnace is the heart of the glass industry. While heavy oil was once used to generate the high temperatures needed, today’s furnaces rely on more environmentally friendly natural gas and electricity. In the future, electric furnaces are expected to become the norm. Regardless of the heat source, once a furnace is started, it must remain at high temperatures continuously. If the temperature drops, the glass inside the furnace and pipes will solidify, causing severe damage. That’s why the furnace operates 24hours a day, 365 days a year, and the entire factory runs in shifts without rest.

For those involved in industrial glass manufacturing, it is taken for granted, but even during holidays like New Year's or Obon, the factory never stops. Without such invaluable labor, the glass for our smartphones would not be manufactured.

If a furnace is shut down and the glass solidifies inside, the cost of repairs is enormous. Therefore, multiple backup systems are in place to guard against natural disasters or power outages.

The “Magic” of Making Ultra-thin Yet Strong Glass

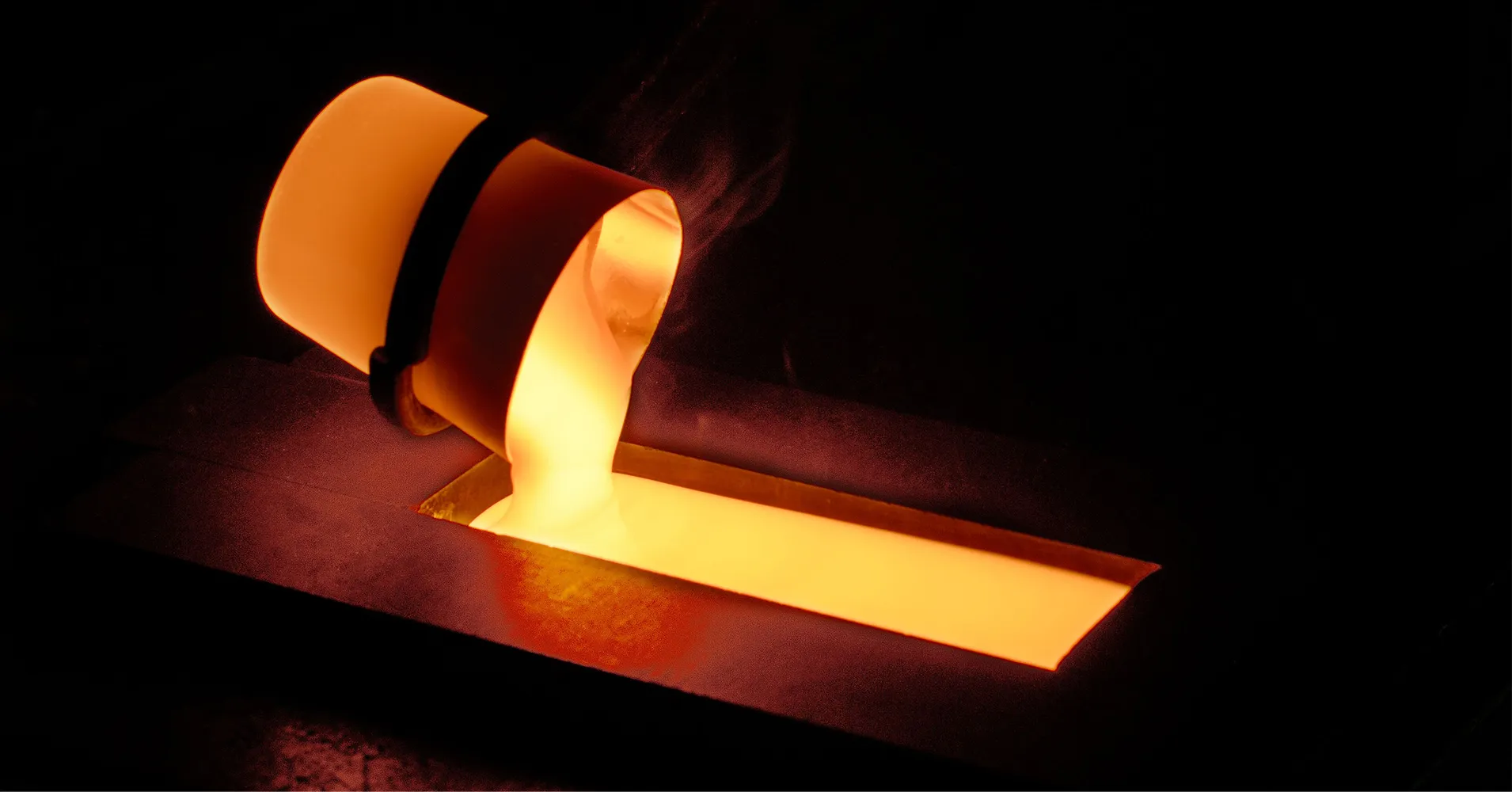

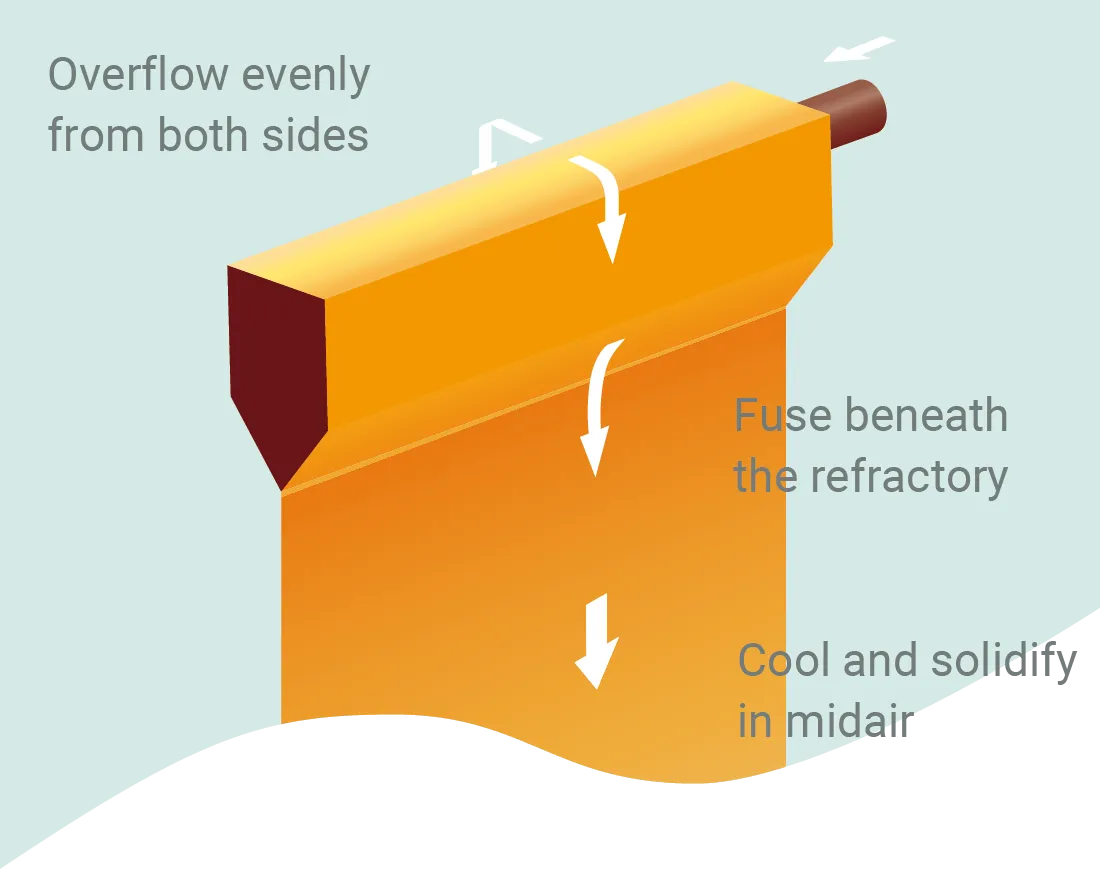

Ultra-thin glass is produced using the overflow method.

Molten glass is poured into a trough-shaped refractory, where it overflows from both edges and flows downward from a height equivalent to an eight-story building. The glass from both edges merges at the bottom and is drawn downward, forming a sheet as thin as 0.05mm or less. By adjusting the flow rate and draw speed, NEG can produce a wide range of glass thicknesses—from ultra-thin smartphone glass to thicker glass for large displays.

Now, imagine how difficult it is to draw 1,500°C molten glass into sheets thinner than 0.05 mm. The trough must be incredibly precise, its edges perfectly level, and the temperature of the molten glass must be meticulously controlled. Even slight temperature variations can cause uneven flow. It is precisely because managing these controls is so challenging that other companies cannot replicate it.

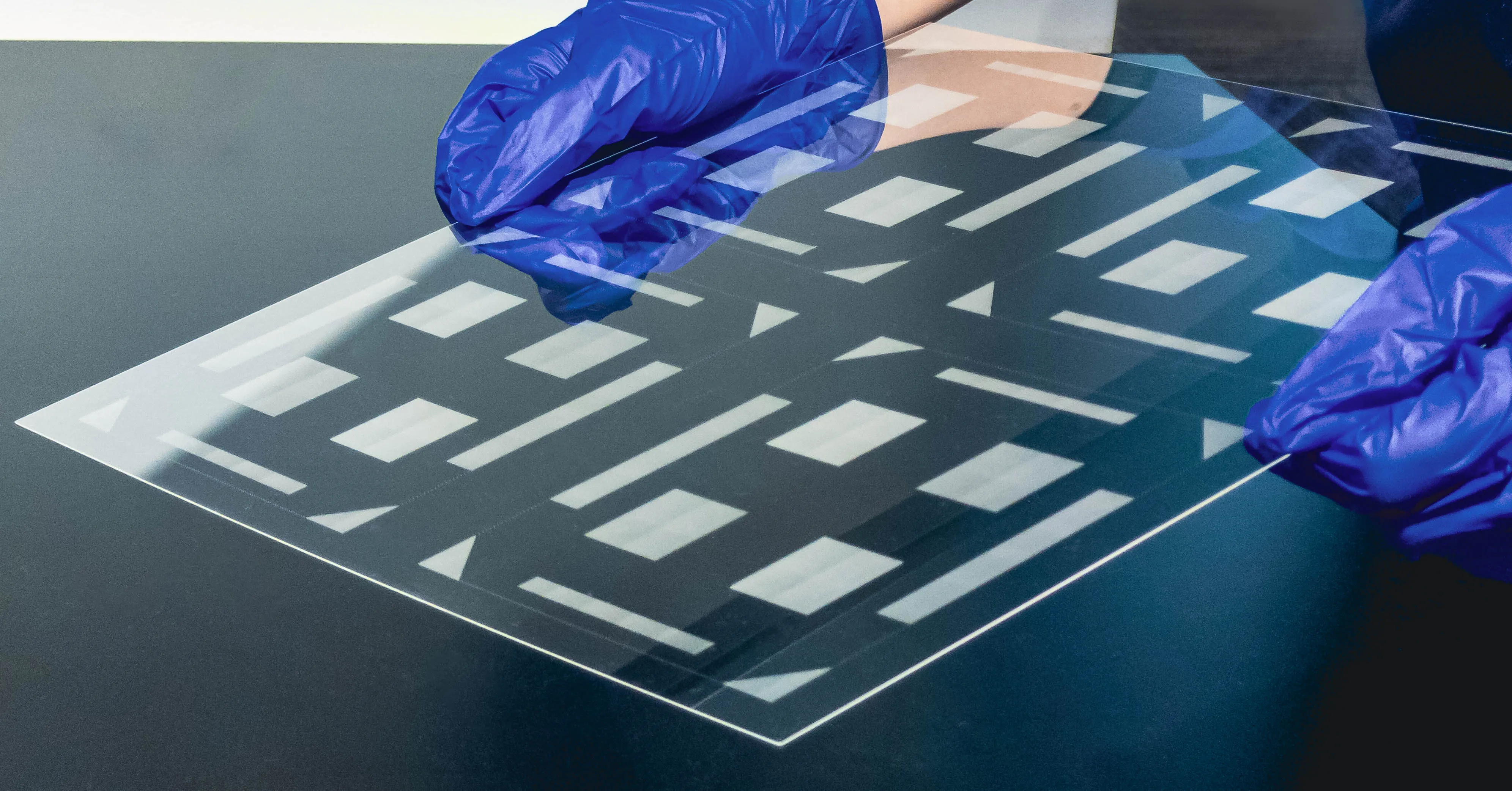

But it is this method that allows them to produce strong, uniform, and extremely smooth glass. Any unevenness in thickness or strength could lead to breakage. Since the glass does not touch any surfaces during forming, there’s no need for post-processing like polishing, resulting in a surface smooth at the nanometer level.

For example, LCD displays require a liquid crystal layer just a few micrometers (1μm = 0.001mm) thick between two glass sheets. Even the slightest bump or scratch can cause display irregularities or “dead pixels.” That’s why extreme smoothness is essential.

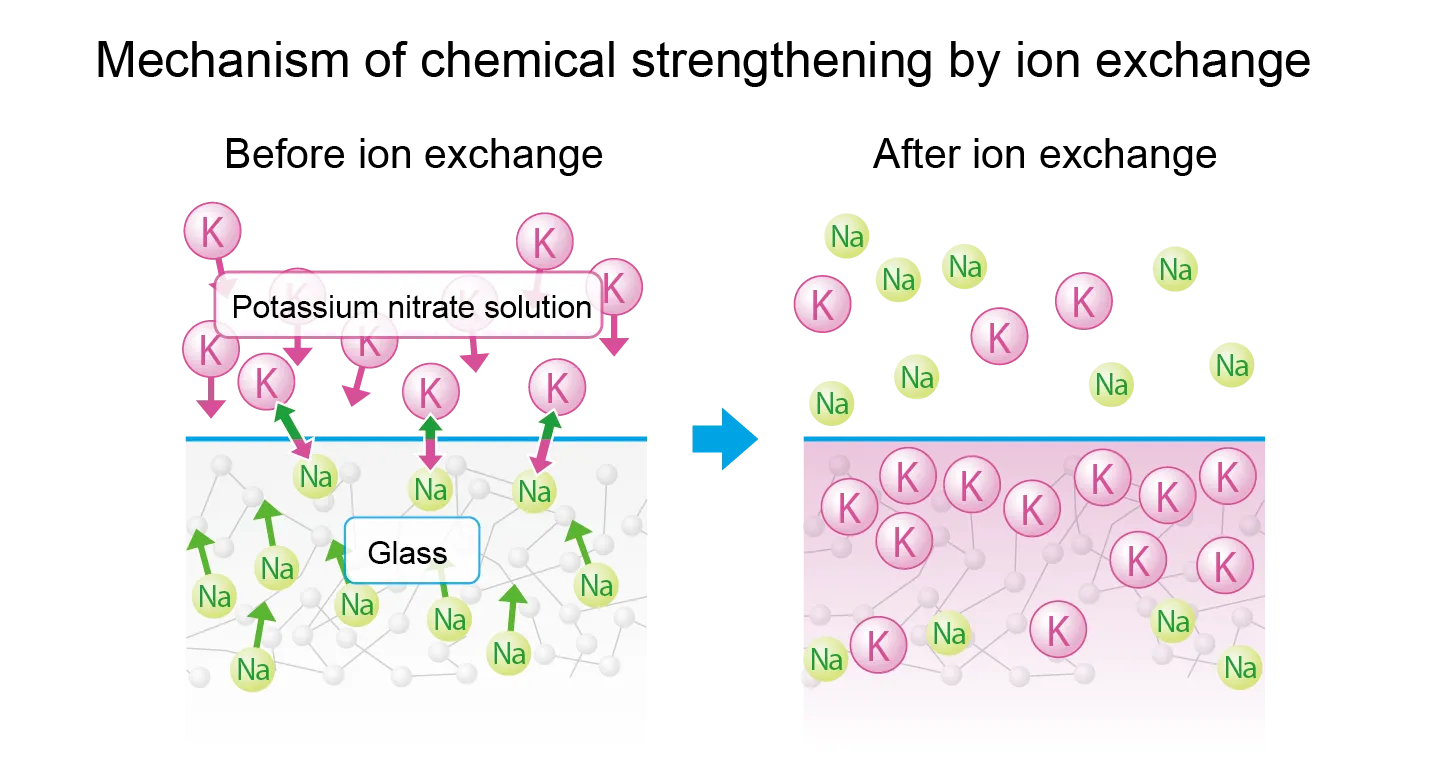

After forming, the cover glass undergoes chemical strengthening, making it tough enough to withstand hammer blows.

Chemical strengthening involves immersing the glass in a potassium nitrate solution. The glass originally contains sodium ions (Na⁺), which are replaced by larger potassium ions (K⁺) through ion exchange. This creates compressive stress on the surface, counteracting the tensile stress that causes cracks, making the glass much harder to break.

Thanks to the precise control of each production step, it’s possible to create smartphone cover glass that combines ultimate strength and thinness.

The History of Overcoming Challenges to Realize the “Magic”

It’s no coincidence that this world-class glass technology is based near Lake Biwa, Japan’s largest lake.

NEG established its factories along Lake Biwa because glass production requires large amounts of water—for cooling the high-temperature furnaces and for various forming and processing steps. The abundant groundwater near the lake is ideal for this purpose.

Let’s take a step back and look at NEG’s history. Like many other companies, NEG has weathered numerous challenges.

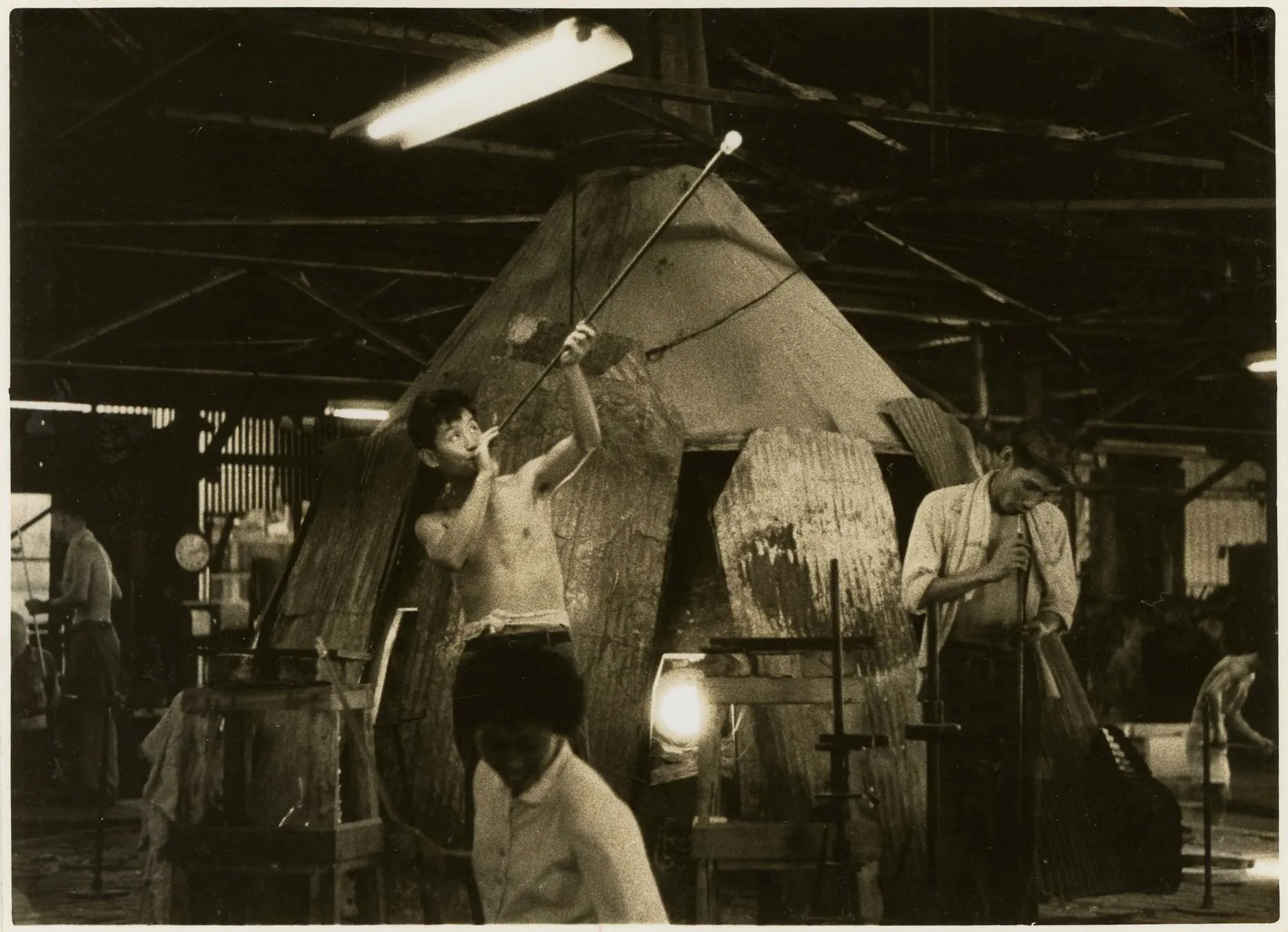

NEG was founded in October 1944 as the glass manufacturing division of Nippon Electric Company (NEC). It was during the final stages of World War II, when vacuum tubes for military radios were in high demand. Shortly after its founding, the war ended, and NEG’s vacuum tube glass became a key technology supporting Japan’s postwar recovery through products like radios.

However, in the mid-1950s, transistors began replacing vacuum tubes in radios, sharply reducing demand. NEG then shifted to producing glass for television cathode-ray tubes (CRTs).

As you may know, TVs were one of the “Three Sacred Treasures” of postwar Japan (along with refrigerators and washing machines). By 1964, TV ownership exceeded 90%, and throughout the 1990s, Japan shipped over 10 million units annually. NEG supplied CRT glass to NEC and other major domestic manufacturers, operating at full capacity.

In the 1980s and 1990s, the company faced another challenge: the strong yen. As Japanese-made CRTs became too expensive, manufacturers moved production overseas. NEG followed suit, building factories in Southeast Asia, North America, and Europe.

Then, in the 2000s, LCDs began replacing CRTs in TVs and monitors, causing CRT demand to plummet. NEG faced yet another crisis but found a new path in producing glass for LCDs.

Initially focused on TVs and computer monitors, NEG eventually expanded into ultra-thin glass for smartphones and other electronic devices. Through continuous innovation, the company perfected the production methods that now yield today’s ultra-thin smartphone glass.

From vacuum tubes to CRTs to display glass, NEG’s products have evolved, but its founding spirit—“contributing to society through the creation of products that support civilization”—continues to live on.

Nano-level Technology Supporting Our Daily Lives

Now that you’ve seen how smartphone glass is made and the historical journey behind it, you hopefully have a clearer picture of its significance.

To achieve the beautiful visuals and responsive touchscreens we rely on every day, smartphones require ultra-thin glass that is both incredibly smooth at the nanometer level and exceptionally strong. Behind this essential component is NEG, operating 24 hours a day, 365 days a year, on the shores of Lake Biwa.

The next time you use your smartphone, take a moment to appreciate the remarkable technology behind the glass in your hand.

Writer: Takuta Murakami

A technology and gadget editor/writer specializing in Apple products like iPhones and iPads. He frequently attends events such as WWDC and iPhone launches in California. With a background in editing hobby magazines, he has produced around 600 issues over 30 years since 1992. Since 2010, he has written extensively on IT topics, including educational ICT, startups, and digital transformation in government. He is the editor-in-chief of ThunderVolt.